Blank spells in children can be normal daydreaming or a sign of Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE). It’s important to tell them apart because CAE needs medical attention.

What is Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)?

CAE usually begins between ages 4 and 10, though it can start a little earlier or later. It occurs more often in girls than in boys. It’s a common type of childhood epilepsy—about 20% of school-aged children with epilepsy have CAE. The exact cause isn’t known, but genetics play a strong role.

What are the signs or symptoms of Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)?

Children with CAE may have many absence seizures every day—sometimes more than 50.

During a typical absence seizure, a child may:

- Suddenly lose awareness

- Stare blankly

- Stop talking or pause what they’re doing

- Missing parts of conversation

- Not respond when you speak to them or touch them gently

- Make small, repeated movements with their fingers, hands, mouth, or eyes (called motor automatisms)

Absence epileptic seizures usually last about 10 seconds and end just as abruptly. Afterward, the child often goes back to what they were doing as if nothing happened. Sometimes they may seem slightly confused for a moment.

Absence seizures are more likely to happen when a child is sitting quietly, tired, or unwell, and less likely when they’re active or focused on something they enjoy.

At first, parents may think these episodes are just daydreaming. But over time, you may notice they happen more often and last longer!

What are the necessary investigations for Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)?

Your child should be seen by a paediatric neurologist for a full neurological assessment. As part of the comprehensive assessment, Dr Yeo may suggest an Electroencephalogram (EEG), which records the brain’s electrical activity.

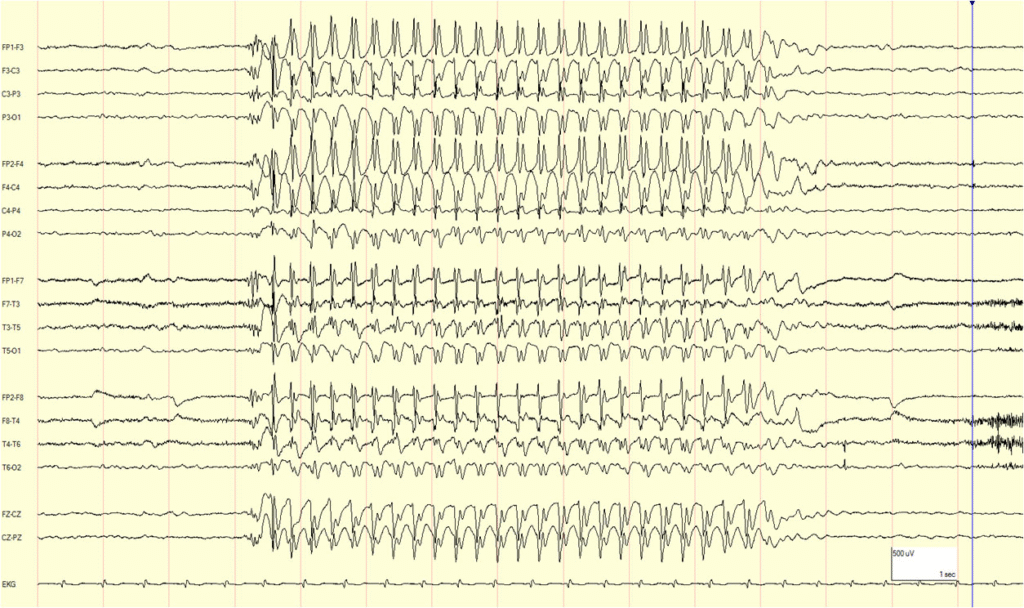

During the EEG, your child may be asked to breathe deeply or quickly (hyperventilate) for a few minutes. This often triggers an absence epileptic seizure in children with CAE and helps confirm the diagnosis. The EEG may show a pattern called “spike and wave” during an absence epileptic seizure.

Usually, no other tests are needed. But if treatment isn’t working well or the diagnosis is unclear, Dr Yeo may suggest more tests, such as an MRI brain scan or genetic testing

What are the potential treatment options?

Anti-seizure medications (ASMs) usually work well for CAE. Dr Yeo or your paediatric neurologist may prescribe one of these:

- Ethosuximide (Zarontin) – recommended first line treatment option

- Sodium valproate (Epilim)

- Levetiracetam (Keppra)

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

Less commonly, medicines like Topiramate or Zonisamide may be used.

Important: Sodium valproate can harm an unborn baby. So if you or your child can become pregnant now or in the future, doctors will usually choose another medicine. If sodium valproate is recommended, the doctor will explain the risks and benefits clearly.

What is the prognosis of Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)?

Most children with CAE have a good outlook. About 60% outgrow it by their early teens.

For some children, CAE can develop into other epilepsy types as they get older, such as Juvenile Absence Epilepsy (JAE) or Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME). If this happens, they may start having other epileptic seizures, such as myoclonic or generalised tonic-clonic seizures.

CAE can sometimes be linked with attention/ concentration, memory, language or learning difficulties. Children with CAE may also have a higher risk of depression, anxiety or other emotional issues. Dr Yeo or your paediatric neurologist can guide you on getting support for these areas if needed.

For more information about Seizures or Epilepsy, please click Seizure & Epilepsy

If you have any further questions, you can schedule an appointment today with Dr Yeo.